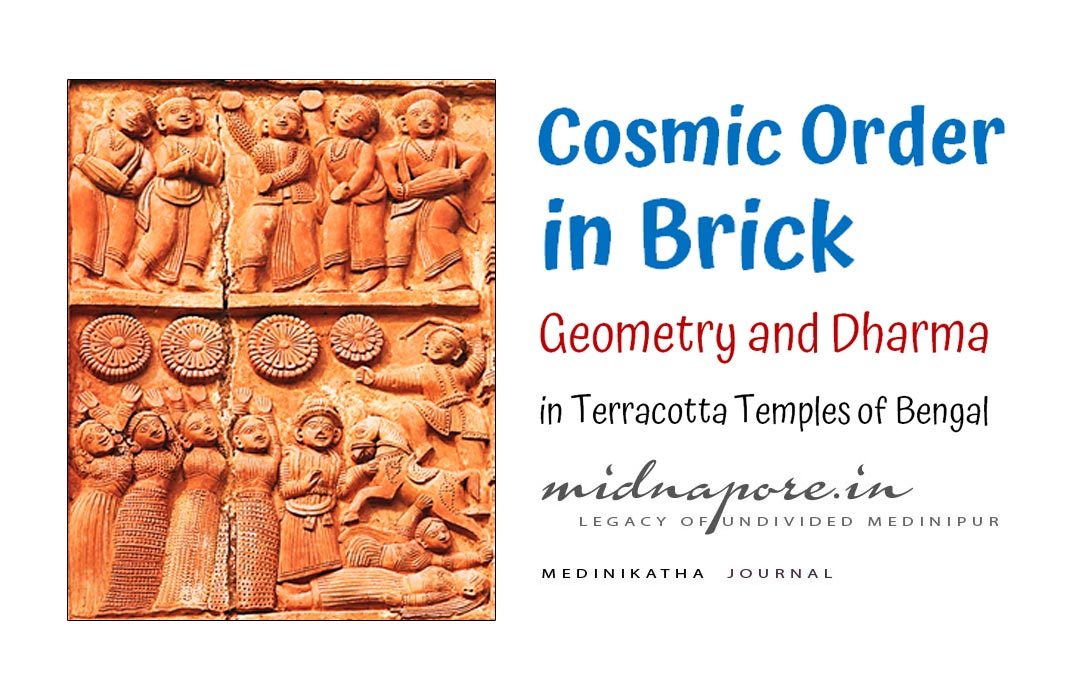

Cosmic Order in Brick: Geometry and Dharma in Terracotta Temples of Bengal

পোড়ামাটির ইটে মহাজাগতিক ক্রম: বাংলার টেরাকোটা মন্দিরে জ্যামিতি এবং ধর্ম

टेराकोटा ईंटों में ब्रह्मांडीय व्यवस्था: बंगाल के टेराकोटा मंदिरों में ज्यामिति और धर्म

Pijus Kanti Samanta

Prakash Samanta

Home » Medinikatha Journal » Pijus Kanti Samanta & Prakash Samanta » Cosmic Order in Brick: Geometry and Dharma in Terracotta Temples of Bengal

Temples as Microcosmic Mandalas

Indian temple architecture is rooted in the idea that space is sacred and can serve as a bridge between the human and the divine. The temples of Bengal, though constructed in clay rather than stone, preserve the core metaphysical intentions of Indian architectural tradition. Each structure is not simply a devotional site but a spatial embodiment of cosmic principles. In these temples, the concept of dharma—as both moral code and cosmic order—is physically rendered through geometry, orientation, and symbolism (Kramrisch, 1946).

Shridhar Temple, Kotulpur, Bankura (Photographed on 24.12.2023)

Sacred Geometry in Indian Knowledge System (IKS)

Sacred geometry in Indian traditions is not decorative but ontological. It serves to align human constructs with cosmic truth. Central to this is the Vastu Purusha Mandala, a geometric grid system representing the universal body. The temple, when constructed according to this mandala, becomes a microcosm of the universe, with each space corresponding to a deity or cosmic principle (Acharya, 1927).

Yantras and mandalas—geometric diagrams symbolizing the divine—are also translated into architectural form. The temple as a whole functions as a three-dimensional yantra, channelling spiritual energy through its proportions and orientations.

Mathematical ratios such as 1:1, 1:2, and the Golden Ratio are carefully embedded in design to ensure cosmic harmony. These ratios govern everything from the layout of the sanctum to the tapering of spires (shikharas), ensuring that sacred form resonates with universal order (Banerjee, 2005).

Historical and Cultural Context

Between the 16th and 19th centuries, Bengal witnessed a flourishing of terracotta temple construction, especially under the Malla rulers of Bishnupur. These temples arose during the Bhakti movement, which emphasized personal devotion and accessibility of the divine. As such, these temples were designed not only for priests but for lay devotees, reinforcing dharma at both personal and communal levels.

The choice of terracotta—a local, sustainable material—shows the integration of ecological wisdom with spiritual intent. In regions lacking stone, artisans turned to clay, mastering it with exquisite skill. Terracotta allowed for intricate storytelling through relief panels depicting epics, deities, and folk motifs, thus transforming temple walls into moral and cosmic narratives (McCutchion, 1972).

Spatial Design as Embodied Philosophy

The spatial design of Bengal's temples follows principles laid out in Vastu Shastra and other traditional texts. The ground plans are typically square or rectangular, representing the stability of the earth, while vertical progression through the temple mirrors the ascent from the material to the spiritual.

Temple orientation—often facing east—aligns the structure with the rising sun, symbolizing enlightenment and renewal. The central sanctum (garbhagriha) represents the cosmic womb, housing the deity at the point of highest energetic concentration. Movement through the temple follows an axial progression, guiding the devotee from the outer material realm to inner spiritual realization.

Temples like Rasmancha and Jor-Bangla in Bishnupur exemplify these principles. Rasmancha, with its 108 chambers and mandala-like layout, encodes sacred numbers and concentric motion. Jor-Bangla, with its double-pitched roofs and symmetrical design, reflects both vernacular influence and cosmic balance (Dutta, 2019).

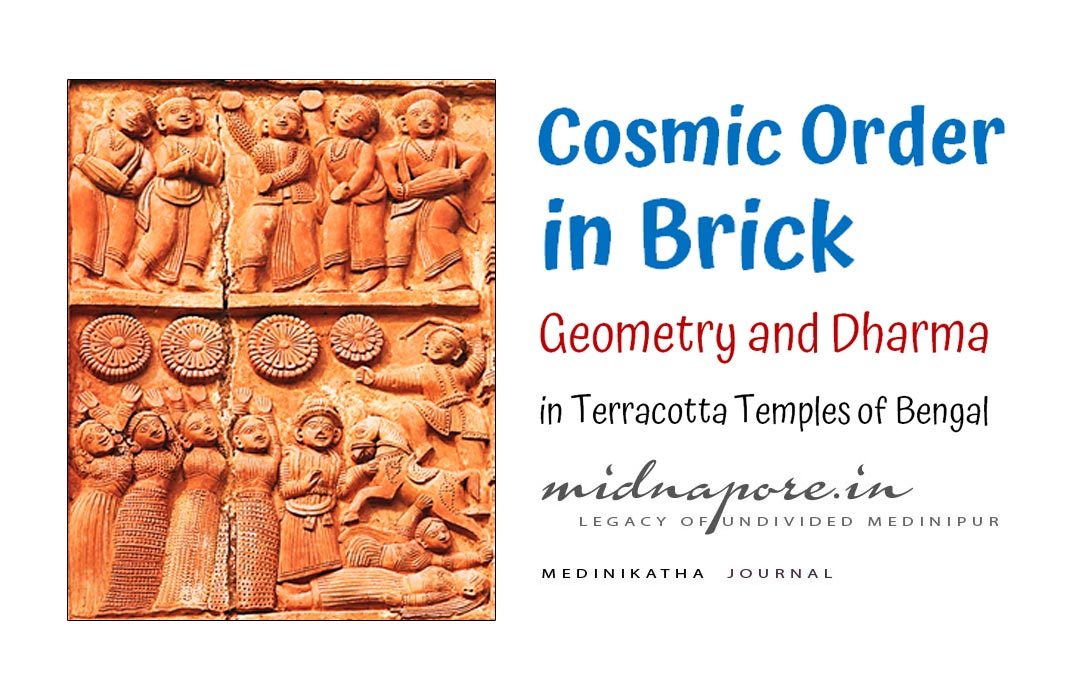

Mathura gamana of Shri Krishna in the terracotta plaque of Shridhar temple

Geometry as Symbol and Narrative

The terracotta decorations of these temples are rich in symbolic geometry. Fractal patterns, repetitive lotus motifs, and concentric panels reflect the infinite continuity of the cosmos. These are not mere ornamentations but metaphysical symbols—echoing the belief that reality is patterned, ordered, and recursive. Sacred numbers such as 8 (Ashta Dikpalas), 9 (Navagrahas), and 108 are repeatedly encoded into temple architecture and iconography. They signify completeness, cosmic directions, and the intersection of the divine with human existence.

Transmission of Knowledge

This geometric wisdom was preserved not through formal schooling but via oral traditions, apprenticeship, and guild-based transmission. Master artisans trained younger generations through practical engagement, mnemonic chants, and ritual instruction. Though ancient texts like the Silpa Shastras were rarely studied directly, their principles permeated through community memory and embodied practice. Guilds ensured continuity, ethical standards, and fidelity to cosmic principles (Bose, 2011).

Geometry and Dharma

The geometry of terracotta temples expresses dharma on three interrelated levels:

• Social Dharma: Temples as community centres foster collective identity and ethical life.

• Ritual Dharma: Spatial precision ensures correct ritual performance and divine alignment.

• Cosmic Dharma: Proportions and orientations align human space with celestial rhythms.

The temple becomes a living map of the universe, where sacred geometry embodies the continuity of the cosmos.

Contemporary Relevance

The use of sustainable materials, geometric efficiency, and spiritual orientation in terracotta temples offers guidance for green architecture and culturally sensitive design. IKS principles can inform contemporary education, particularly in architecture, heritage conservation, and mathematics. By reviving these ancient traditions, we can create spaces that are not only functional but spiritually and ecologically aligned—preserving heritage while fostering innovation.

Conclusion

Bengal’s terracotta temples, with their integration of sacred geometry and spatial philosophy, are more than architectural marvels—they are embodiments of dharma. They reflect a worldview where the built environment is a reflection of the cosmos, and where each proportion and alignment sustains harmony between the human and the divine.

By revisiting these traditions, we uncover timeless lessons in sustainable living, ethical design, and the sacredness of space—ensuring that the wisdom of Indian Knowledge Systems continues to guide contemporary thought and practice.

M E D I N I K A T H A J O U R N A L

Edited by Arindam Bhowmik

(Published on 08.06.2025)

Reference -

1. Acharya, P. K. (1927). Architecture of Manasara. Oxford University Press.

2. Banerjee, S. (2005). Geometry in Indian Temple Design. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

3. Bose, S. (2011). Craftsmen and Kings: Artisans in Indian History. Permanent Black.

4. Dutta, B. (2019). Vastu in Terracotta Temples of Bengal. Marg Publications.

5. Kramrisch, S. (1946). The Hindu Temple. Calcutta University Press.

Please share your valuable feedback in the comment box below.